Hall of Shame: My embarrassing connection to Cooperstown

With the Baseball Writers’ Association of America revealing the 2021 Hall of Fame results this week (or lack there of), I was once again reminded of my own connection to Cooperstown: my great-granduncle, Roger Bresnahan, is considered to be one of the least deserving member of the Hall of Fame.

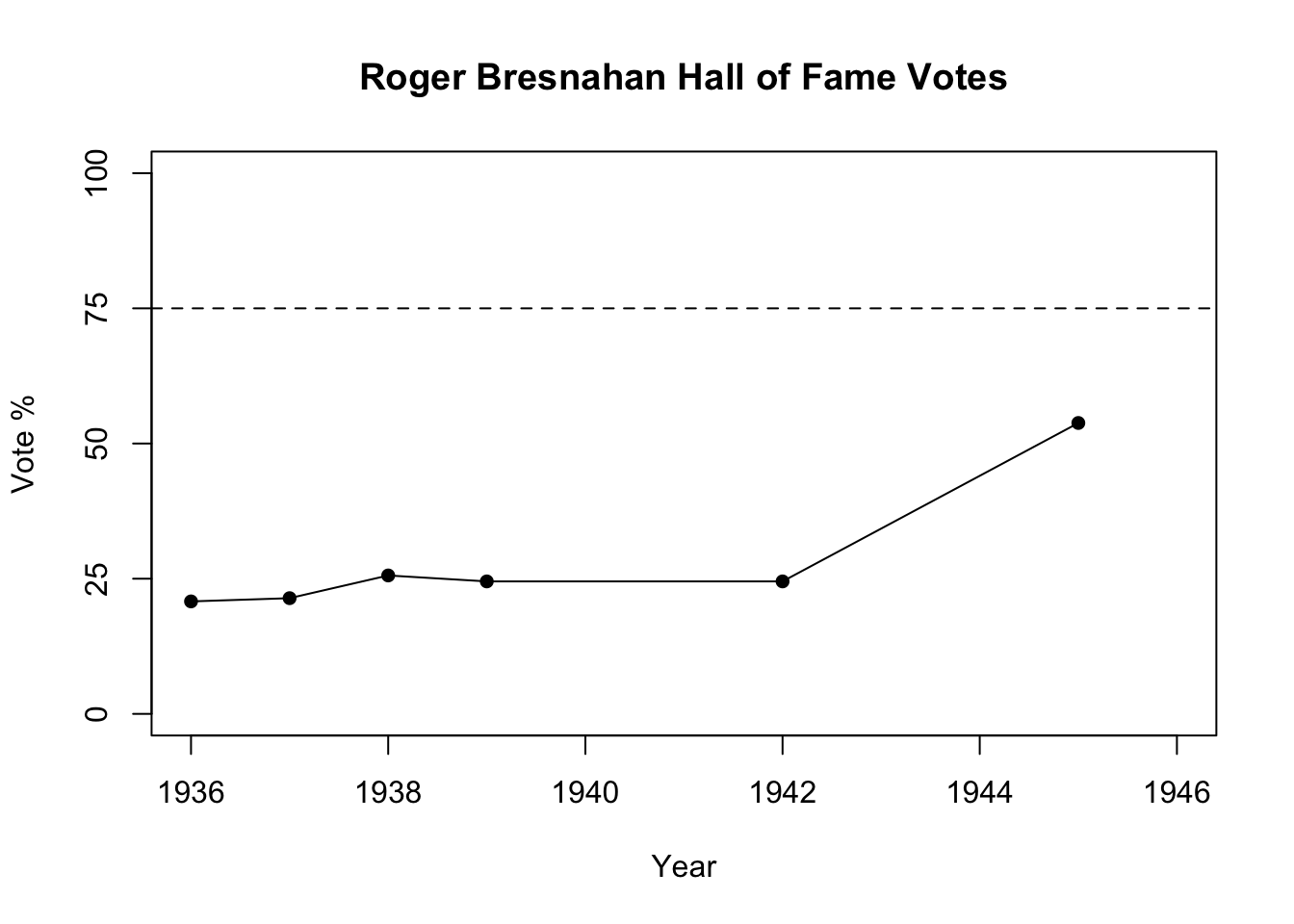

Roger played catcher from 1897 to 1915 for five different teams, winning the 1905 World Series with the New York Giants, but is most famous for being the first MLB player to wear shin guards (and getting made fun of for it). He had a .279 career batting average and never brought in more than 56 runs in a season. So how was he voted in? The figure below shows that he, well, wasn’t. Roger appeared on 20-25% of the ballots the first five years he was eligible before reaching 53.8% in 1945. This spike had very little to do with appreciation for his career though and was instead a response to his untimely death just a month before voting took place. The Permanent Committee, perhaps mistaking this show of goodwill as some sort of exponential trend, stepped in a few months later and added him to the inducted class.

So there you have it, my great-granduncle is in Cooperstown because of bad data analytics. Bill James, the famed statistician, is quoted as saying just as much, claiming Bresnahan “wandered in the Hall of Fame on a series of miscalculations” and reiterated the point in a 2008 interview with Freakonomics, listing him as one of the 10 players that shouldn’t be in the Hall.

But how good was he really? I’ve always believed these assertions without looking into his stats with the proper context. To remedy this, I decided to look at his best and most average seasons (in terms of OPS+) and try to compare him to players from the 2019 season. To aid the comparison, I calculated z-scores for several major stats to control for spread, as suggested in Dan Lependorf’s Hardball Times article.

Bresnahan’s best season came in 1903 when he put up a 160 OPS+ for the Giants, tying him with Honus Wagner for third place in baseball. That translated into a slash line of .350/.443/.493 with 87 runs and 55 RBIs in 113 games. After converting these stats to z-scores and comparing them to the qualified batters in 2019, I found that Anthony Rendon had the most comprable season, with the two measuring up to their peers similarly in terms of slash line and runs per game. Rendon put up .319/.412/.598 with 117 runs and 126 RBIs in 146 games that season, which was good enough for third in MVP voting. Bresnahan performing at that level would have made him the star of the team, perhaps he had a Hall of Fame career after all.

| Player | Year | Average | OBP | Slugging | R/Game | RBI/Game |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roger Bresnahan | 1903 | 1.97 | 2.48 | 1.81 | 1.53 | 0.32 |

| Anthony Rendon | 2019 | 1.75 | 2.16 | 1.74 | 1.84 | 2.33 |

This season was somewhat of an aberation however, as Bresnahan averaged a 126 OPS+ for his career. The best proxy for this average was 1907, when he had a 128 OPS+. He played 110 games for the Giants that year and hit .253/.380/.360 with 57 runs and 38 RBIs. Looking at 2019, the player that best matches this output is Carlos Santana, who hit .281/.397/.515 with 110 runs and 93 RBIs in 158 games. The table below shows the comparison isn’t as tidy as the one above but they put up similar OBP and slugging numbers and weren’t too far off in terms of runs and RBIs per game either. Santana earned an all-star nod and a Silver Slugger award for his output that season, honors that, achieved annually, would place Bresnahan as one of the best players in the game.

| Player | Year | Average | OBP | Slugging | R/Game | RBI/Game |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roger Bresnahan | 1907 | -0.27 | 1.58 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.04 |

| Carlos Santana | 2019 | 0.32 | 1.68 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.22 |

Taken together, these comparisons paint Uncle Rog as a perennial All-Star that, at his best, could garner MVP support. All at a position that typically lacks offense! Does this translate into being one of the best 19 catchers of all time, though? No, probably not… But it’s not as far-fetched as I once believed.

And besides, Cooperstown has made worse decisions.

(Photo: “Out at home” by Boston Public Library is licensed under CC BY 2.0)